Narrative in Architecture: Architects as Storytellers

On the one hand, architecture as a thing of the mind, a dematerialized or conceptual discipline with its typological and morphological variations, and on the other, architecture as an empirical event that concentrates on the senses, on the experience of space’ (Tschumi, 1999: 83).

FIG. A: Ideal Space

FIG. B: Real Space

THE ARCHITECTURAL PARADOX:

In his 1975 essay ‘The Architectural Paradox’, Bernard Tschumi explored the conflict inherent to the nature of architecture and how it relates to space. The paradox is as follows: it is impossible to question the nature of space and at the same time experience it. When trying to define space, Tschumi highlights the discrepancy between ‘ideal space’ (that which is rational and realised quantitatively) and ‘real space’ (or sensed space that is a result of perception). ‘Ideal space’ is conceptual and sees space as an object with boundaries and limitations, belonging to the school of physics and mathematics (Fig. A). It can be controlled and seen from every angle and is perhaps the conception of space that architects would like to work with (Tshcumi, 1999). ‘Real space’ is created through experience. For example, consider how an individual would perceive being in a building; the space is not made up of a plan or section but rather consists of the smell of the plaster, the feel of the earth beneath the feet, the memories evoked by the shadows dancing across the wall (DiMascio, 2014). It is subjective, messy and unique to each individual, and doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with an architect (Fig. B).

THE PARADOX AND ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION:

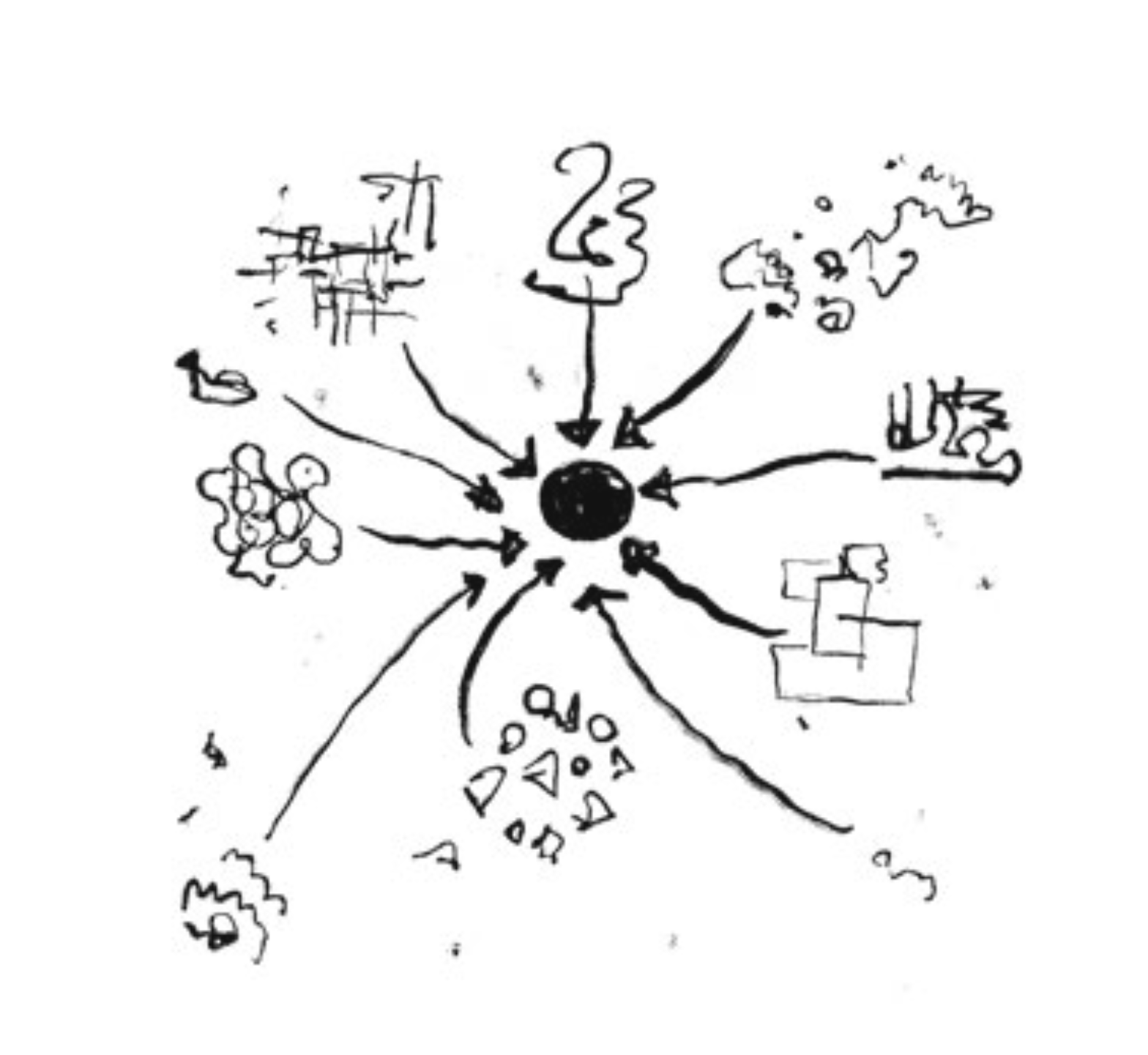

FIG. C: Collation

Architectural education has to contend with this dualistic nature of space. On the one hand, students are taught the basics of construction and communication: how to lay foundations, how to draw a wall detail, how to lay out a plan. Yet they are also expected to explore the intangible impacts of a project: the social, cultural, and political consequences, the history of a site and how this relates to an intervention, the communities that will be impacted, and the relationships within them. In this way architecture starts to encompass everything, and so to root it to a discipline, the powers that be, i.e. RIBA and the heads of school state that all these explorations must be captured in a building. Yet as Tschumi writes, “the achievement of architectural reality (building) defeats architectural theory while at the same time being a product of it.” (Tschumi, 1999: 226) This, then, is the essence of the paradox: it is impossible to adequately capture the entirety of conceptual architecture within a built project, but if not, is it still architecture? It could be argued that the struggle to deal with this paradox has eroded architectural education to a point where it is perceived by some to lack both the rigour of academia and the precision of an applied science (Green, 2003). The design studio sits as an anachronism within the university system, producing architecture graduates who are a jack of all trades yet masters of none.

EXPERT GENERALISTS, SPATIAL STORYTELLING AND THE POWER OF NARRATIVE:

FIG. D: Narrative Journey

To complete the saying, ‘A jack of all trades is a master of none, but oftentimes better than a master of none.’ Perhaps the key to relevancy for the architecture graduate lies in embracing this aspect of the subject and becoming ‘expert generalists.’ As generalists, architects can place themselves in the middle of a crowded room and collate information from multiple sources (Fig. C). They can then arrange this information into a narrative and present it back to a diverse audience. In this way, they become spatial storytellers (Lyu, 2019). Architecture, like literature, is rooted in the narrative in that there is a narrator (the architect) and a reader (the user) who perceives a created world sequentially like the pages turning in a book, or a journey through a building (Fig. D) (Psarra, 2009: 68). Storytellers are not experts in one field. Rather, they are communicators who see the whole, draw links between disparate points, and then have the potential to plant seeds of inspiration that can lead to innovation when cultivated collectively. This moves away from viewing the architect at the top of a power pyramid, dictating the what, where, and when. Instead, the architect becomes part of a participatory process that involves a diverse array of people from multiple fields and with different interests. This in turn leads to the potential for innovation, or multiple innovations, as the problem is disseminated amongst a group (Fig. E).

By creating a narrative, the architect can ignite that most human of instincts: emotion. Emotion allows us to become attached to something, to be inspired, to be riled up and to place ourselves within a narrative (Fig. F). This is important in engaging individuals who hold deeply entrenched views. By allowing them to see themselves as characters in a narrative, the learning of new information becomes less of a ‘this is how you should do it’ experience, and instead can become an empowering process as the new interpretation of the information comes from within.

FIG. E: Participation

FIG. F: Emotion

BEYOND ARCHITECTURE:

We live in a post-truth society, where scientific fact has become subjective, and narrative is all-important in engaging a polarised audience. Expert generalists have the potential to create narratives in a whole range of fields including those outside of the design world. Scenario development (otherwise known as storytelling) is a tool employed in urban design to respond to critical challenges such as the climate crisis that are incredibly complex and cross multiple interacting political, social and biophysical scales and disciplines. Participatory scenario development can offer diverse solutions whilst also fostering a sense of ownership and engagement in both the creation and implication of these solutions (Johnson, 2012). Architectural techniques have also been employed in investigative journalism to build narratives that highlight global atrocities and injustices, for example in studios such as Killing Architects and Forensic Architecture (Killing, 2018)( Mandolessi, 2021). Narrative development also has an important part to play in policy development and adoption. The COVID epidemic has relied on coherent messaging from the state with varying levels of efficacy, as politicians struggled to strike a balance between individual emotion and scientific fact. Perhaps more architects should have been involved (Mintrom, 2020) as it is clear that the profession constantly deals with the junction between the technical and the emotive.

The ability to weave a coherent narrative, backed up with quantitative fact, is essential in today’s mass-information society, and architects can find their place not just working in the built environment, but as storytellers across many fields.

SOURCES:

Tschumi, B. (1999), Architecture and Disjunction, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Psarra, S., 2009. Architecture and Narrative: The formation of space and cultural meaning. Routledge.

Lyu, F., 2019. Architecture as spatial storytelling: Mediating human knowledge of the world, humans and architecture. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 8(3), pp.275-283.

DiMascio, D. and Maver, T., 2014. Investigating a narrative architecture: Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art.

Johnson, K.A., Dana, G., Jordan, N.R., Draeger, K.J., Kapuscinski, A., Olabisi, L.K.S. and Reich, P.B., 2012. Using participatory scenarios to stimulate social learning for collaborative sustainable development. Ecology and Society, 17(2).

Killing, A. (2018), Building Digital Stories: Architecture and Cartography Meet Documentary and Journalism. Archit. Design, 88: 30-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2339

Mandolessi, S., 2021. Challenging the placeless imaginary in digital memories: The performation of place in the work of Forensic Architecture. Memory Studies, 14(3), pp.622-633.

Mintrom, M. and O’Connor, R., 2020. The importance of policy narrative: Effective government responses to Covid-19. Policy Design and Practice, 3(3), pp.205-227.

Green, L.N. and Bonollo, E., 2003. Studio-based teaching: history and advantages in the teaching of design. World Transactions on Eng. and Tech. Edu, 2(2), pp.269-272.